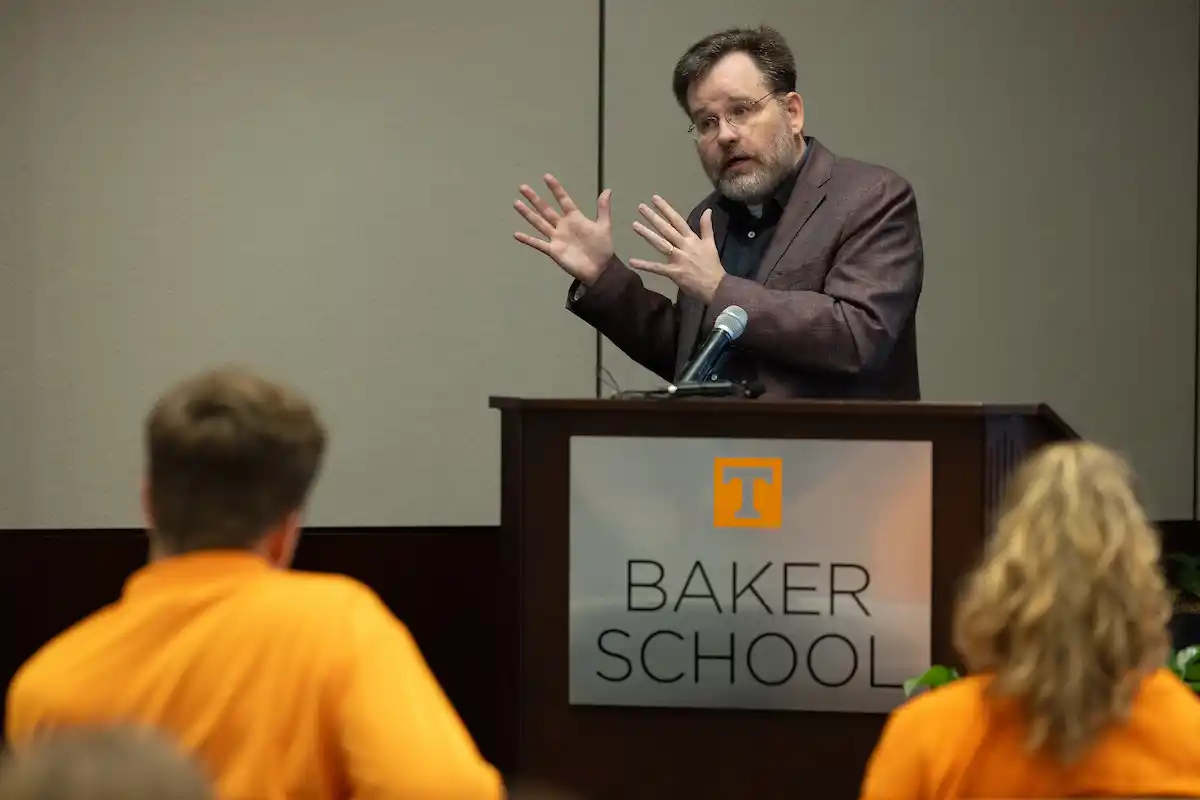

Constitution Day with Yale Professor of Law Keith Whittington

In celebration of Constitution Day, the Institute of American Civics (IAC) at the Howard H. Baker Jr. School of Public Policy and Public Affairs (Baker School) at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, hosted Keith Whittington, the David Boies Professor of Law at Yale Law School. Whittington’s teaching and scholarship span American constitutional theory, American political and constitutional history, and free speech and the law.

He started the day by giving a lecture to students in IAC’s Engaging Civically course. The lecture centered on his 2018 book Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech. A hot topic on college campuses over the last year, Whittington provided the historical framework on both faculty and student free speech movements for universities that led to academic freedom.

Universities were not complex speech environments when they were first created, and there is a specific reason for that. Early institutions held more restrictive purposes, predominantly the training of ministers, which played a large role in what was said on campuses and what faculty taught in the classrooms. Students’ role at universities was to learn.

That radically changed when institutions began to look at understanding what the goal of universities should be, which meant looking at what professors were teaching in classes. The change also came with the creation of more institutions and funding coming from different sources. What came out of that was the purpose of universities to operate on the very frontier of knowledge. Students needed to be taught across various fields, asking them to explore the unknown. That meant that professors needed the freedom to research and study all those areas, even the controversial ones, to teach and challenge their students without the fear of losing their jobs.

Academic freedom had only related to the faculty up until the 1960s. The pressure of students’ free speech movement on campuses grew out of anti-war and civil rights protests. Students demanded the right to explore so-called controversial ideas outside the classroom. It was in the mid-1970s that both faculty and students began to have protection of free speech.

In the afternoon, Whittington joined the IAC’s Board during their quarterly meeting. He gave a presentation about the founding of the Academic Freedom Alliance (AFA) and his role as chair of the academic committee. The AFA is an alliance of college and university faculty members dedicated to upholding the principles of academic freedom.

In the evening, an audience of over 300 students, faculty, and the public filled an auditorium at the student union to listen to Whittington speak on the questions of how the Constitution works, how we should be interrupting it, and what the future of the court and constitutional interruption might be. He set the table by giving general thought to constitutional interpretation and defining originalism.

Interpreting the Constitution has always been a critical question of the Court. After the 1970s and 80s, scholars started to rethink the emphasis on living constitutionalism, which dominated American scholarship and American jurisprudence through most of the 20th century. They started to go back to the Constitutional text and look at how the text itself should be interpreted. This led to a return to thinking on the role of judges, which is looking at the actual text in front of them and interpreting it to the best of their ability and according to appropriate interpretive rules, then applying it to the case that is in front of them.

In his lecture, Whittington referenced the definition of interpretation as stated by scholars, which is the art of finding out the true sense of any forms of words that in the sense their author intended to convey and enabling others to derive from the same idea which the author intended to convey. Ultimately, the act of interpretation is a form of communication. It is trying to understand what somebody is telling you. With the Constitution, the point of interpretation and the point of the judicial enterprise is to think through what the framers who drafted it were trying to accomplish, what they were saying, and the rules and texts they were laying down. Then learning how to unpack all of that and try to apply them in the situations that we are now confronting.

Throughout his lecture, he covered many different angles on interpreting the Constitution but focused on Originalism, which emerged from theories developed over the years by scholars, refocusing their attention on the text of the Constitution and how to understand it and its meaning. Originalism has developed since it first surfaced in the 1970s; it was first a political project but has since become an academic project. But at its core, it is the same; what we ought to do with the text is to think of it as an act of communication – what were the founders trying to say when they drafted it?

It was a fitting end to a full day of lectures and presentations in celebration of Constitution Day.